Marylanders love their unique flag. But do they know its association with the Confederate cause?

Benjamin Jancewicz does not pay for HBO, and he is not a native Marylander. He grew up on a First Nation reservation in Canada. But this past July, when he learned the creators of Game of Thrones were in talks to bring a controversial new series Confederate, which revisits the Civil War and imagines a present in which the South had won—to the cable giant, he began noodling around the internet for the backstory of Maryland’s flag. His interest in the state’s ubiquitous flag, as a graphic designer, and Maryland’s conflicted role in the Civil War, as an activist, naturally intersected and piqued his curiosity. Like many non-natives, he also admits to some bewilderment at Marylanders’ unbridled love for their flag.

Almost immediately, Jancewicz found information linking the red-and-white quadrants of the flag—and the cross bottony contained therein—to the Confederate cause. Maryland soldiers fighting for the South often pinned the cross bottony to the lapels of their gray uniforms. And local citizens caught wearing the colors red and white during the war, or dressing their babies in such, could be charged with treason. “It’s not tough to dig this stuff up,” he says. “It’s right there on the state’s website.”

Jancewicz’s first tweet that night was intentionally provocative:

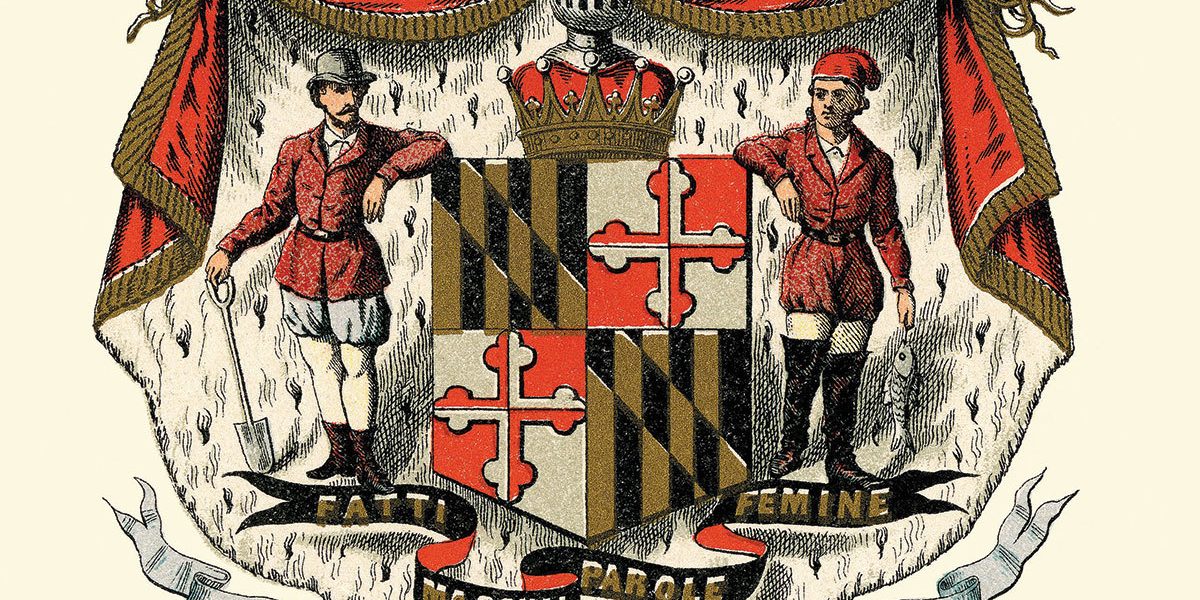

He posted in the same Twitter thread that, after the war, Maryland tried to reconcile its split personality by creating its first official state flag—the one we admire today—in 1904. It combines the black and gold paternal Calvert crest—associated with the Union during the war and the flag of Baltimore City today—with the red and white crest of the maternal side of the Calvert family, which had been co-opted by the Confederates. (The Calverts, notably George, son Cecil, and grandson Charles—the first three Barons of Baltimore—were the founding family of the Maryland colony.)

The backlash was swift. Right-wing news outlet Breitbart caught wind of Jancewicz’s viral tweet and published a rebuke. Red Maryland, a conservative group, began a “Save Maryland’s Flag” petition. Gov. Larry Hogan declared the flag would not be changed on his watch. TV and radio stations interviewed Jancewicz, who received threats.

“More than anything, I think the response demonstrated two things: Most Marylanders don’t know the history of their flag,” Jancewicz says. “And that for all the people who say flags and monuments don’t matter, they are obviously important to a lot of people.”

Then, the controversy died as quickly as it had arisen. There was no broad call for the flag be redrawn. (Not that Jancewicz advocated one; he only encouraged people to learn its history.) We simply hold it too dear. At least for now.

The short answer to the question, “Does part of the Maryland state flag have ties to the Confederate cause?” is easy. Yes. Easy answers to other questions are more elusive. Because Maryland Confederate sympathizers and soldiers embraced the colors of the maternal side of the Calvert coat of arms (created in England in the early 17th century), does that mean the flag is forever tainted? When claims are made that the Maryland flag was created to “reconcile” Union and Confederate sides after the war, is that true?

Or, is it better understood as an attempt by white, Southern-sympathetic state legislators to assert their prominence? Certainly, the creation of the state flag was not an effort to repair the harm of two and a half centuries of slavery in Maryland to African Americans. Even at the time the legislators were claiming to bring together opposing sides of the war (nearly four decades after its conclusion) by formally adopting the flag, attempts were made by state legislators to disenfranchise black voters.

The bigger question may be whether Maryland should fly any flag paying homage to the Calvert family—either black and gold or red and white. The founding family’s record on race is shameful. In 1639, under Cecil Calvert—the second Lord Baltimore—Maryland became the first colony to specify baptism as a Christian did not make a slave a free person, as it did in England. In 1664, led by the third Lord Baltimore, plantation owner and Proprietary Governor Charles Calvert, Maryland became the first colony to mandate lifelong servitude for all black slaves, the first to make the children of slaves their master’s property for life, and the first to ban interracial marriages.

Still, it is hard to overstate the popularity of the Maryland banner. There’s a store in Hampden, Baltimore in a Box, whose entire brick rowhouse exterior has been painted to replicate the flag. There is an enormous unfurling during University of Maryland football and basketball games.

The flag can be seen on beer koozies, bikinis, beach blankets, T-shirts, key chains, cycling jerseys, and winter hats. On Twitter, Jancewicz posted a compilation of state flag tattoos.

Indeed, before Baltimore in a Box had finished the repainting of their Hampden home, an image of the massive Maryland flag storefront popped up on reddit with appropriate kudos: “T-minus 24 hours until Baltimore’s [Instagram] models come out in droves to pose in front of this.”

“People walking down ‘The Avenue’ in Hampden take pictures of it all the time without ever even in coming in,” says store owner Ross Nochumowitz. “Marylanders love the state flag. They think it’s perfect.”

To locate the origin of our admired state banner, you need to drive an hour north of London to St. Mary’s Church in Hertingfordbury, England. The design that would form the basis of our flag is inside the medieval stone chapel there, atop the beautiful funereal tomb of Anne Mynne, the first wife of George Calvert, who died, it is believed, while delivering the couple’s 11th child.

On one side of the mantle behind the marble sculpture of her body—lying in repose in a flowing gown, her head resting on a tasseled pillow—is the unmistakable black and gold crosshatching of the paternal Calvert crest. On the other side of the mantle, toward her feet, is the Mynne family crest—red and white with what is known as the cross bottony (a Christian symbol with each arm terminating in three rounded lobes).

“It is a moving tribute from George Calvert to his wife,” says Henry Miller, a historical archaeologist and director of research for St. Mary’s City. “And you can’t help but be impressed when you see the Maryland colors there together.” When Miller leads tours of Marylanders interested in the state’s English roots to Hertingfordbury, the sight of Anne Mynne’s tomb and what would eventually become Maryland flag, he says, “is always the highlight of that trip.”

Digging past the Confederate question for a moment, there is also a smaller controversy around the maternal family origins. Most Maryland texts refer to the red and white and cross bottony quadrant as the “Crossland banner” or “Crossland arms,” in reference to George Calvert’s mother’s family—the Crosslands—and not to his wife Anne Mynne’s family. But that appears to be up for debate given the visual evidence at Anne Mynne’s tomb. Ed Papenfuse, the former Maryland state archivist, believes it’s a mistake passed down through the years before the documentation of the Mynne family crest at George Calvert’s wife’s tomb.

There is still no evidence to date, however, that explains why the Southern sympathizers in Maryland—some 25,000 men joined the Confederate Army—embraced the red and white quadrant and cross bottony. It is known that Maryland’s U.S. Union troops often stitched the black and gold Calvert emblem, more closely associated with the North, into their uniforms. So it may have just been a logical response by Confederates to co-opt the other half of the founding family of Maryland’s coat of arms. Conveniently, red and white were also colors strongly associated with the Southern cause. There is also the possibility that the cross itself imbued a certain religious crusade quality to the Confederate effort in the minds of its faithful.

Whatever the case, the cross continued to turn up as a Confederate symbol. It became the focal point of an ornate iron gateway in front of the Maryland Line Confederate Soldiers’ Home in Pikesville. And crosses bottony are fixed to the tombstones of Confederate soldiers in Maryland and monuments to Maryland’s Confederate soldiers at the Gettysburg battlefield. Also known: In 1945 the General Assembly mandated that a gold cross bottony—that Maryland Confederate symbol—is the only ornament that can be mounted above the state flag. In 1983, a version of the flag was put onto state license plates. From time to time, the red and white colors and cross bottony are still flown by neo-Confederates.

“For Marylanders, it was a very potent symbol of the Confederacy,” Papenfuse says. “But it was not created to serve the Confederacy. It was created to honor the important role of women in the Calvert family.”

Indeed, the heartbreaking inscription on Anne Mynne’s tomb from her husband, George, who went into seclusion from grief after her death, describes his wife of 18 years as “a woman born for all outstanding things.” “The bottom line, to me,” Papenfuse says, “is that its meaning has other aspects beyond its sad connection to the Confederacy.”

The flag, similar to Confederate monuments in the state, “are toxic and stressful to deal with, but we have to talk about them and deal with them,” says Morgan State University associate professor Lawrence Brown. “They are directly linked to racist policies put in place in the past—in fact, they were part of the animating effort that built support for those policies—many of which still exist today.”

Brown doesn’t believe there will be widespread demand to change the flag unless people on one side start using the red and white banner at their rallies, in the same way the Confederate flag is used. “Then, I think you’ll see pushback. Same thing with the Francis Scott Key monuments [Key, a slave owner and anti-abolitionist, included a lesser-known, pro-slavery stanza in his ‘Star-Spangled Banner’]. If they become a rallying point for white supremacists or the KKK, then there will be conflict and pushback.

“You can’t predict which way the river of history will turn, or where the rapids will appear,” Brown continues. “It is important to dismantle the symbols of racism, but that is not the end goal. It is more important to dismantle the polices they represent.”