The Baltimore City Health Department understands the assignment.

Over the past week, the department’s social media presence has garnered widespread applausefor the way it’s using epidemiologist-endorsed memes to spread accurate information online about the coronavirus—including the delta variant, why you shouldn’t drink bleach to cure COVID-19, and an explainer on this past spring’s Johnson + Johnson vaccine pause.

It’s a clever initiative. Memes, the good ones anyway, spread easily and speak directly to a particular moment in time. Black social media users are often the driving force of meme culture, and Black Americans are also less likely to be vaccinated, at least in part due to limited access to vaccines and valid distrust. And while the number of Black folks getting vaccinated in Baltimore has been trending upward, only 35.5 percent of Black residents are fully vaccinated.

Within this circumstance, Adam Abadir, the communications director for the city’s health department, saw an opportunity to dispel misinformation and bolster all the work being done on the ground by, as he says, talking to people in their own language.

I spoke with Abadir and Benjamin Jancewicz, a consultant for the health department who works on the COVID-19 social media campaign, about how it came about, meme culture, and why they chose those specific names for the characters in their ads. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Julia Craven: The ad campaign reminds me of meme culture. Was that intentional?

Abadir: Absolutely. Memes are the language of the internet. And what we’re trying to do is be a part of that conversation—and it seems to be working. We’ve been pushing out information like this before the vaccine was widely available—harm reduction principles, wearing a mask, keeping six feet of distance, and that kind of stuff. We kept getting questions from our followers on social media who were doing these things about how to convince friends and family members to do them as well.

Back in February, there was this really viral moment where Mayor Brandon Scott was addressing activist Shorty Davis at a press conference. Davis’s mask was sort of falling under his face. So Scott said, “Shorty, pull your mask up.” It was this really cool moment. It taught us that there’s an opportunity to tell people how to practice harm reduction principles if we come at them from a slightly different angle. We can totally message how to stay safe during a pandemic if we’re meeting people where they are and if we’re using language that they use themselves. So that was when we started using names as a vehicle to start introducing concepts.

Later on that transformed into dealing with some misinformation head on.

Jancewicz: What we were finding is that a lot of people wanted to have these conversations with the people around them, with their friends and family, but they didn’t always feel the best equipped. They didn’t know exactly what to say. At the health department, we’re able to drive through all that with an ice breaker and really break it all apart. That’s what we saw our mayor doing. He was speaking very directly, in plain English, and that’s what people are trying to do when they have these conversations with the people around them.

There’s all this apprehension and, really, respectability politics around trying to have these conversations. And we decided to go through with a wrecking ball, and just say, “No, this is not OK.” And you don’t have to put up with it. These actions have real consequences. That’s the energy behind it.

How did you come up with the specific scenarios for the ads? Because they are very specific. Like, my Nana always had a soda and some crackers around when my stomach was hurting.

Abadir: That one was personal to me. If you’re feeling sick, drink some ginger ale, eat some crackers, and go lay down on the couch and watch The Price Is Right. It’s real. It’s real authentic conversations that we’re having. We were seeing online conversations happen about what people believe will protect them. People are very open and honest on the internet about how they feel about the vaccines, about how they want to “protect themselves” from COVID.

We’re not trying to insult your grandmother here. Grandma had a great point: Medically, ginger can totally reduce your upset stomach, but that’s not the same as protecting yourself from a pandemic that killed millions.

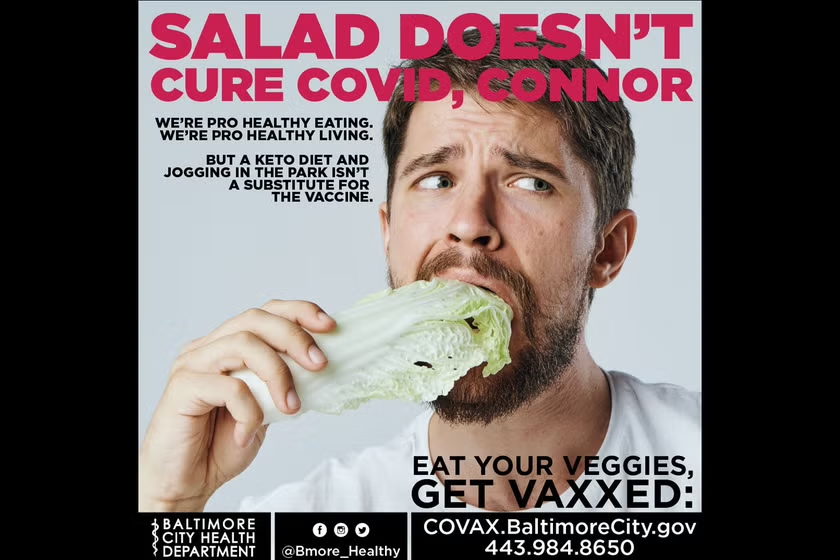

Jancewicz: Some of the conversations were brought to us. The ad we did saying “Salads don’t cure COVID, Connor!,” was inspired by a troll that had come into our mentions. They were saying, “I don’t need your vaccine. I’m on this keto diet. I’m eating my kale and I’m working out,” and all that stuff. We started taking the trolls’ language, feeding it back to them, and pointing out how ridiculous they sound. And using that in ways that made everybody else laugh.

We found that humor is a fantastic tool to deal with this kind of stuff, because when people are trolling us and saying these kinds of things, they’re already at a certain level where feeding them raw information isn’t going to get to them. But diffusing the situation and making them laugh actually works. And we have found—over and over again at this point—that sometimes when we are able to make our trolls laugh, we’re able to start conversations with people who would otherwise be our enemies.

Abadir: One of the weird quirks of social media is sometimes you aren’t sure if the person you’re engaging with is actually a real person or if they’re a bot. We try to distinguish people who have legitimate questions about vaccines from an anti-vax troll whose sole mission is to discourage other people from getting vaccinated.

Are these conversations happening online, in-person, or both?

Abadir: Our social media strategy is only one component of an overarching, larger communication strategy. One of the things that the health department has been doing for months now is standing up our value ambassadors. These are folks who are door-knocking in communities with low vaccination rates and have been trained, gone through focus groups paid by the health department, and they are representatives of the communities that they’re going into.

Not all of these conversations are going to be online and so we need that nuanced, face to face interaction.

Jancewicz: All of these different levels of contact feed each other. We have meetings where we talk to the people who are out at the vaccination clinics, the needle exchange programs, and all of these various outreach points in our community. They talk about what’s happening in the communities. We talk about what’s happening online. This cross conversation allows us to say, “This is a conversation that’s happening right now in Baltimore, we should address it online.” Or, “This is a conversation that’s happening online. We should address it in the field.”

The names—Connor, Debra, Derrick—align really well with the scenarios and characters. How did you come up with them?

Abadir: I know people named Derrick. I know people named Debra. These are based in real world scenarios, and real conversations that people are really having. It’s less of a science, and more art.

Jancewicz: It very much runs in the vein of “Becky” and “Chad.” There are names that people will use in clapbacks automatically and we wanted something that expanded that range a little bit, but was also very, very Baltimore. The names we picked are names that you’ll hear in and around Baltimore—to the point where on Facebook people will tag people they know with the same name in the posts. We’re having multiple levels of conversation. We’ve even had people who are named Debra say, “I’m vaccinated but I know some Debra’s who aren’t. Let me share this.”

We talked about Karen, but honestly, it’s a little too on the nose.

Abadir: People ask all the time—especially about mimosas for brunch—why didn’t we name her Karen, but that’s not what we’re doing here.

After the ads went viral, I saw critiques from several prominent physicians and public health experts, who said the ads are shaming people for believing misinformation about COVID.

Abadir: We don’t want to shame anyone for believing misinformation, but we want them to know that it’s misinformation. That is a slight difference. But, you know, at the end of the day, it’s hard to explain a joke to someone who doesn’t think it’s funny. And that’s OK, because we’re more than just jokes. We’re the health department. It’s not about tone. It’s about preventing hospitalizations. It’s about keeping people alive. It’s certainly criticism that we can take, but the goal isn’t to shame—it’s to explain that that thing you think is going to work is not and, this time, the stakes are higher.

How effective would you say the campaign has been at convincing unvaccinated people to get vaccinated?

Abadir: Unfortunately we don’t have the ability to say if someone went to a vaccination clinic directly because of a meme. But we see it in the sum of all the work that we’re doing. One of the really cool things about the Baltimore city health department is how intentional we’ve been since day one about vaccine access. We’ve taken the stance that we need to bring vaccines where people are. That means setting up mobile vaccination clinics in areas with low vaccination rates. We announced a vaccine home program where folks can make an appointment if they have trouble leaving their home for whatever reason, and our teams will come to you.

Even though we’ve seen a slowdown nationwide in terms of vaccination rates, Baltimore city’s percent increase in individuals getting vaccinated each week is consistently one of the highest in the state. We credit that to all the things we’re doing to reach people.