In the months leading up to the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines in the U.S., Adam Abadir fielded many questions about best practices from Baltimore City residents.

As the communications director for the city’s health department, he observed that many people were already following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidance for things such as social distancing and masking. But they often contacted the department seeking advice for the most effective ways to have conversations about public health recommendations with others.

Then, in January, Abadir and his colleagues watched as Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott said to a community activist at a news conference: “Shorty, pull your mask up.”

That viral moment fueled a realization for Abadir and Benjamin Jancewicz, who creates graphics and runs the department’s social media channels: Sharing information in a new way that isn’t confrontational, they noticed, would likely result in more people spreading the message.

The city’s creative social media push to encourage vaccination, using graphics with phrases such as “What the FAQ is delta?,” comes as much of the country experiences a spike in coronavirus cases. As of Friday, 64.5% of Baltimore City residents have received at least one vaccine dose.

“If you package information in a new way, that’s not as confrontational, but also a little bit funny, you’re much more likely to see that work spread,” Abadir told WTOP. “That was the genesis of the idea of using memes as a way to communicate harm reduction principles.”

The county has used that approach since early April, when it shared a graphic promoting social distancing that said, “Love your elders? Prove it.” Jancewicz said the post was part of the county’s “Get Like Me” campaign, aimed at encouraging vaccination among the city’s youth after city leaders noticed a dramatic difference in vaccine uptake in younger residents.

In an attempt to speak directly to the city’s youth, Jancewicz used lyrics from a rap song and a generic photo of a grandmother.

“We used a rather traditional-looking grandmother who’s got a smirk on her face to encourage younger folk to step up their game a little bit, and have it be a bit of a competition,” Jancewicz said. “’If I can get vaxxed then you can get vaxxed’ type of thing.”

Each new idea has several requirements: It has to be funny; it has to address a real community concern, and it has to include language that people use themselves and will share in their social circles.

Before vaccines were available, the pair used social graphics to promote safety tips, aiming to communicate that a considerable amount of community transmission occurred in restaurants and during house parties. Around the Easter holiday, a separate graphic encouraged testing.

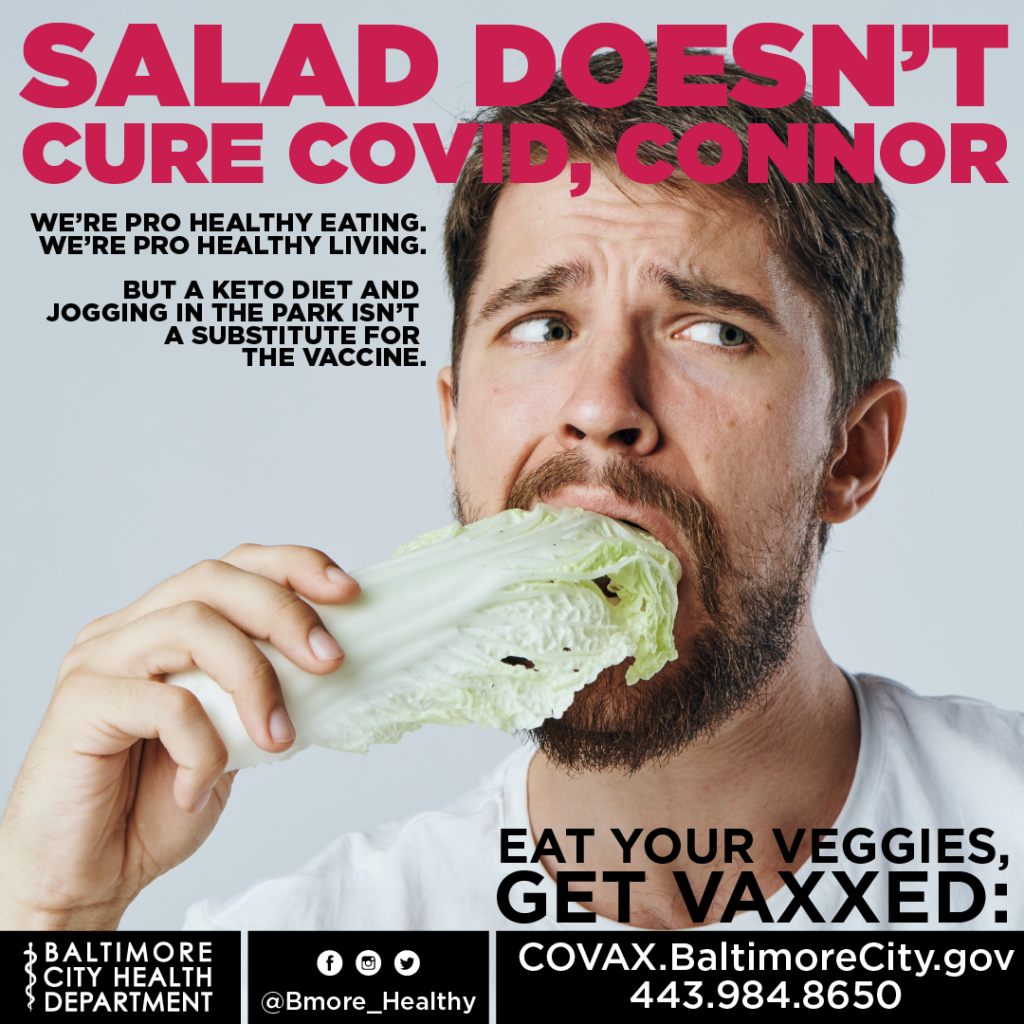

One of the department’s more popular graphics came after a commenter wrote they were on a keto diet and frequently ate vegetables, so a vaccine wasn’t necessary to bolster their immune system. As a result, a graphic that says, “Salad doesn’t cure COVID, Connor” was crafted.

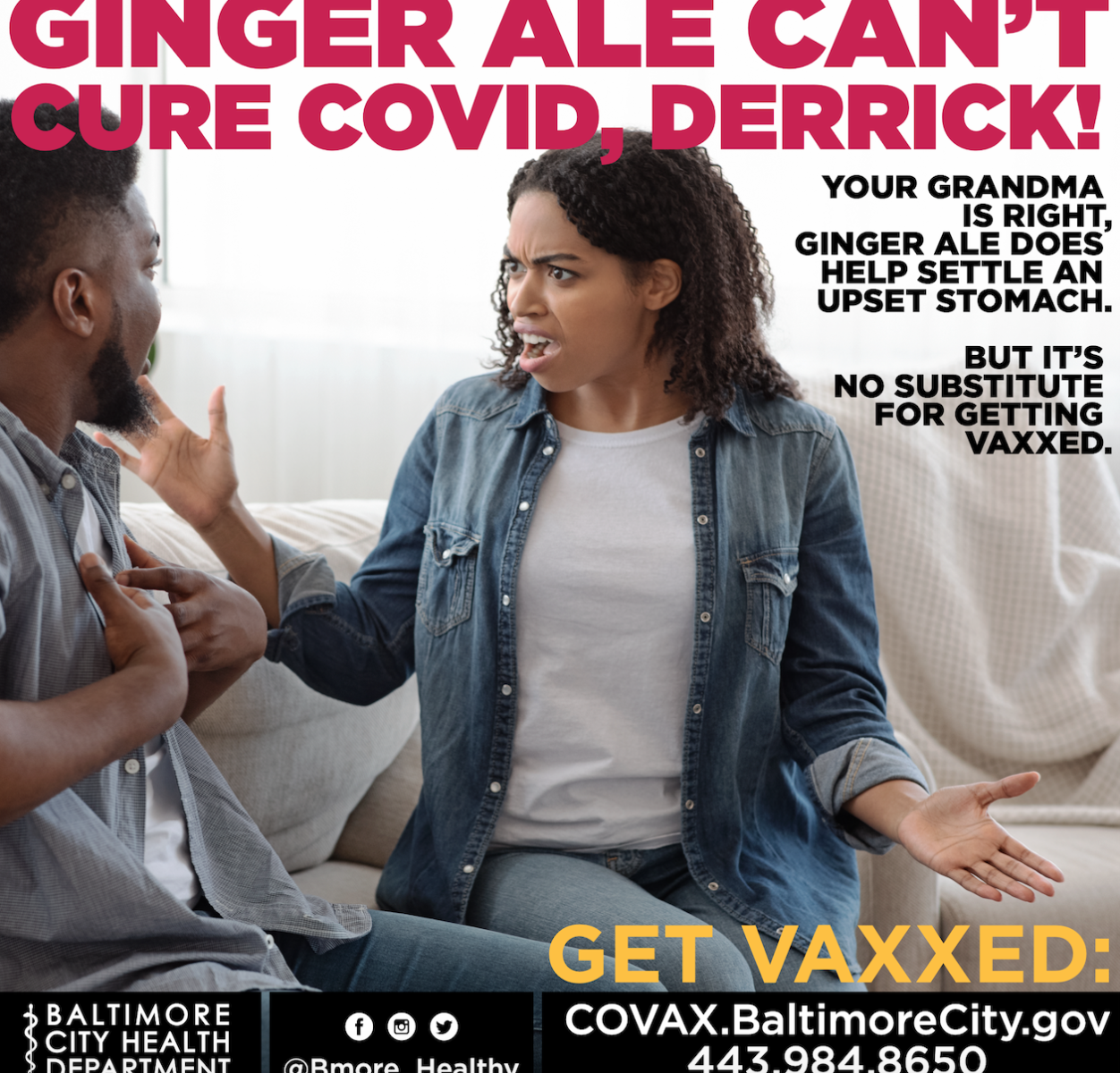

And that type of messaging has evolved into other graphics, such as another that says, “Ginger ale doesn’t cure COVID, Derrick!”

“A lot of these trolls that we have clapped back at find the humor in the things that we’re saying,” Jancewicz said. “[And they’ll say], ‘I actually did have some serious concerns, and I wanted to talk to somebody about that. … These are really icebreakers and they work really well.”

Most recently, the pair launched a series of infographics describing what’s known about the delta variant. While many experts and those in medical circles have explained it, Abadir said, few have been able to share what it means for people in simple terms. Hoping to clear confusion about a complicated topic, the department created a series of informative slides, beginning with one titled “What the FAQ is delta?”

The post with the graphics has 1,400 Facebook comments and has been shared more than 50,000 times.

“We wanted to make sure we give them something that not only they can laugh at, but that they can share with their friends,” Abadir said. “Because they may know somebody that doesn’t follow the rules, or doesn’t pay attention to the latest update from the Baltimore City Health Department.”

The department is always considering the best ways to share information with the public, Abadir said, and Jancewicz witnessed the success of the latest initiative firsthand. While waiting in line with his daughter at a recent vaccine clinic, Jancewicz overheard a few workers speaking in Spanish about ads they had seen in the local Spanish newspaper.

They were some the department’s memes that had been translated, and the messaging evidently worked, since the group was also in line to get vaccinated.

“It’s one thing to be able to see all of the follower counts climb, and be interviewed by different news organizations,” Jancewicz said. “But to actually see people in line for vaccination because of the stuff that we did is really, really cool.”